- Luxor Attractions

- Shoroq Samir

Hatshepsut Temple in Luxor

The mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut of Dynasty XVIII was built just north of the Middle Kingdom temple of Mentuhotep Nebhepetre in the bay of cliffs known as Deir el-Bahri. In ancient times the temple was called Djeser-djeseru, meaning the ‘sacred of sacred’. It was undoubtedly influenced by the style of the earlier temple at Deir el-Bahri, but Hatshepsut’s construction surpassed anything which had been built before both in its architecture and its beautiful carved reliefs. The female pharaoh choose to site her temple in a valley sacred to the Theban Goddess of the West, but more importantly it was on a direct axis with Karnak Temple of Amun on the east bank. Also, only a short distance on the other side of the mountain behind the temple was the tomb that Hatshepsut had constructed for herself in the Valley of the Kings (KV20).

Hatshepsut Temple

The Temple of Hatshepsut was built on three terraced levels, with a causeway leading down to her Valley Temple (now lost) which would have been connected to the River Nile by a canal. Gardens with trees were planted in front of the lower courtyard.

Hatshepsut Temple Interior Design

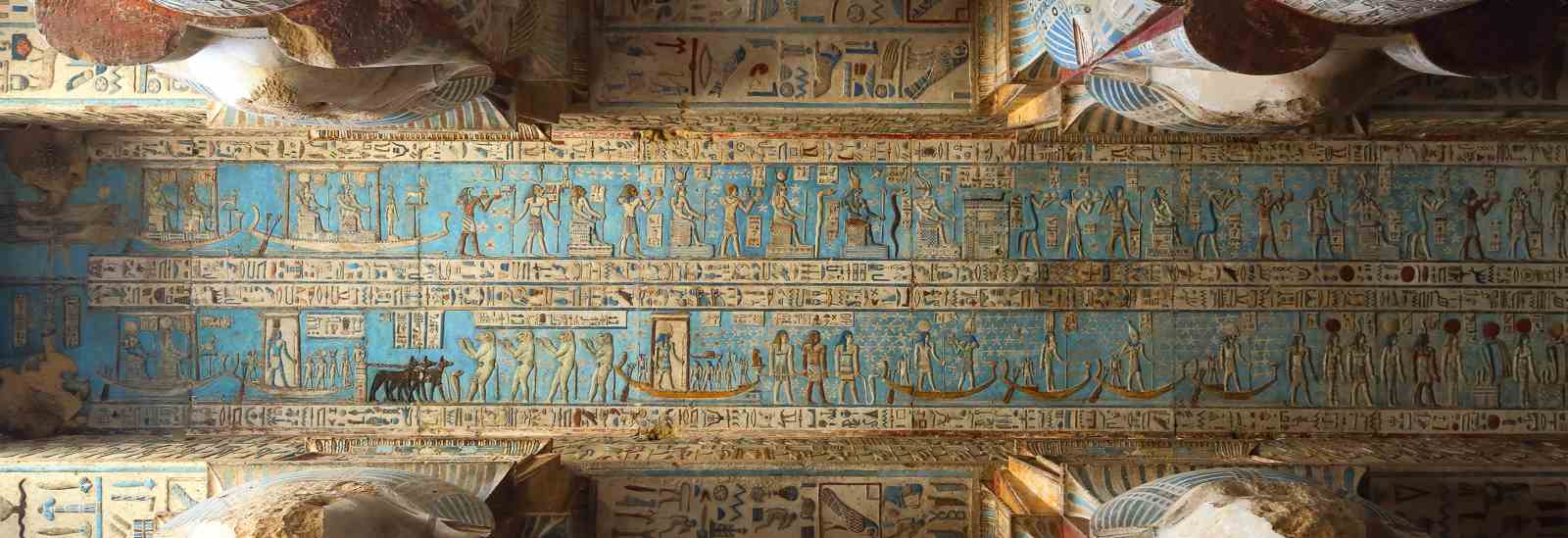

On approaching the first court there are colonnades on the southern and northern sides of a ramp leading to the second court. At the end of the northern colonnade a colossal statue of the queen has been reconstructed and re-erected from fragments. Reliefs in the southern lower portico are very shallow and often difficult to see, but if the light is right they are very interesting. These show the transportation by ship of two obelisks from the granite quarries at Aswan, escorted by soldiers, standard-bearers, musicians and priests. Further along the wall but even more difficult to recognize, the queen offers the obelisks to Amun at Karnak along with the dedication ceremonies.

The lower northern portico shows Hatshepsut in a boat, fowling and fishing in ritual scenes with birds, and a net of waterfowl drawn by two gods. Other rituals scenes include the queen offering statues and driving calves to Amun and she is also portrayed as a sphinx trampling her foes.

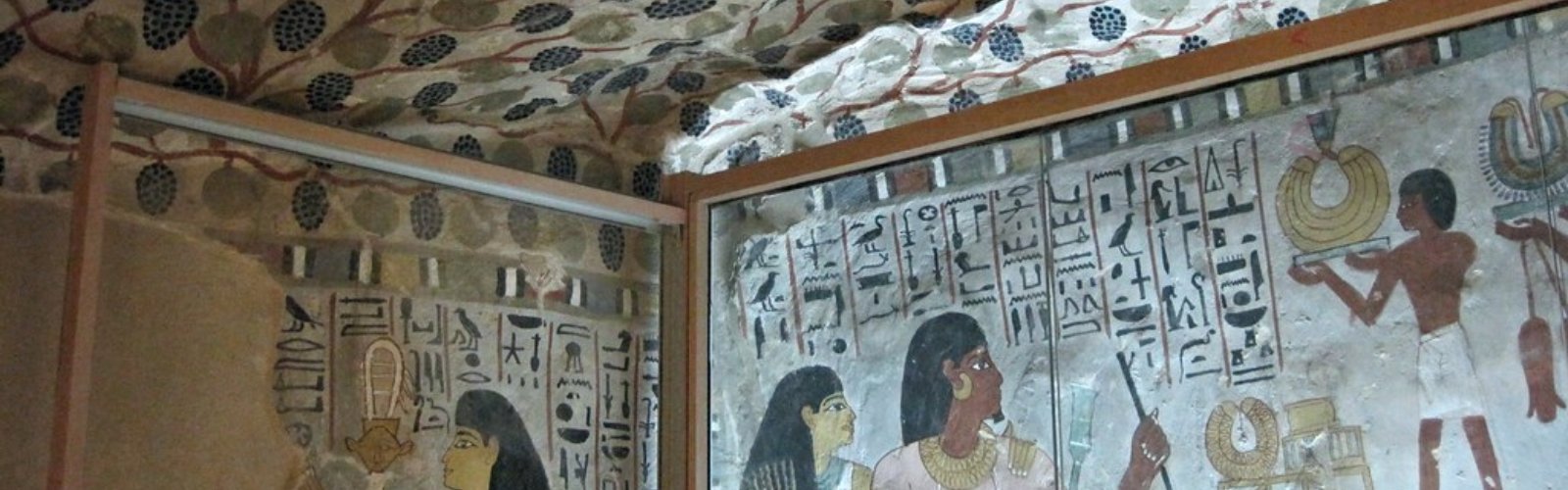

Crouching lions are carved at the bottom of the ramp leading to the second terrace. In the second court, there was once a brick temple dedicated to Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari, but it was destroyed when Hatshepsut’s architect Senenmut began construction of the new temple. A brick shrine dedicated to Aesclepius by Ptolemy III (also destroyed) stood in front of the southern side of the portico on the second terrace. At the very end of the southern portico is a Chapel of Hathor with many reliefs of Hatshepsut being licked or suckled by the goddess in the form of a cow. Beautiful Hathor-headed pillars line the central part of the hall and lead the way to the sanctuary area of the chapel cut into the hillside at the back. Unfortunately, these inner chambers are usually closed to visitors. On the northern wall in the hypostyle of the Hathor Chapel are colourful scenes of boats and a parade of soldiers, a panther and Libyans dancing in a festival of Hathor.

In the southern colonnade is the famous scenes of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt. The precise location of Punt is not known, but it is thought to have been probably on the east coast of Africa, to the south of Egypt. The end wall shows a village in the land of Punt, its dome-shaped houses on stilts with ladders to access them. There are wonderful birds and animals all around. Men are cutting trees, including incense and ebony and carrying off heaps of tribute and treasure to be taken back to Egypt. The famous relief of Ity the ‘Queen of Punt’ – a grotesquely fat lady who was actually the wife of Parahu, Punt’s chief – is now in Cairo Museum but has been replaced by a reproduction. On the western wall, elaborately-rigged sailing boats get ready to bring the tribute back to Egypt, including incense trees in baskets, cattle, baboons and a panther. Note the many types of fish in the water in the register below. Further along, we see the transplanted incense trees in the gardens at Karnak and the produce from the expedition being weighed and documented by officials before being presented to the queen to be offered to Amun.

The northern colonnade begins with a Chapel of Anubis which echoes the Hathor Chapel on the southern side and shows colourful scenes of Hatshepsut in the presence of the jackal-headed god. In some places, Hatshepsut’s figure has been removed but the figure of her successor Tuthmose III remains in offering scenes to Amun as well as Anubis, Wepwawet, Sokar, Osiris and other mortuary gods.

In the northern portico we see scenes of the queen establishing her right to rule by illustrating her divine birth. The reliefs are shallow and not well-preserved but show the divine union of Hatshepsut’s mother Ahmose with Amun. Khnum the creator god then fashions the queen and her ka on the potter’s wheel and Ahmose is led to the birth-room by the goddess Hekat who presides over childbirth. Hatshepsut is then presented to Amun and a number of other deities and the goddess Seshat, with Hapi, records her name and reign length. The register above portrays the coronation ceremonies of the queen where she is crowned first by her father Tuthmose I, then by Horus and Set.

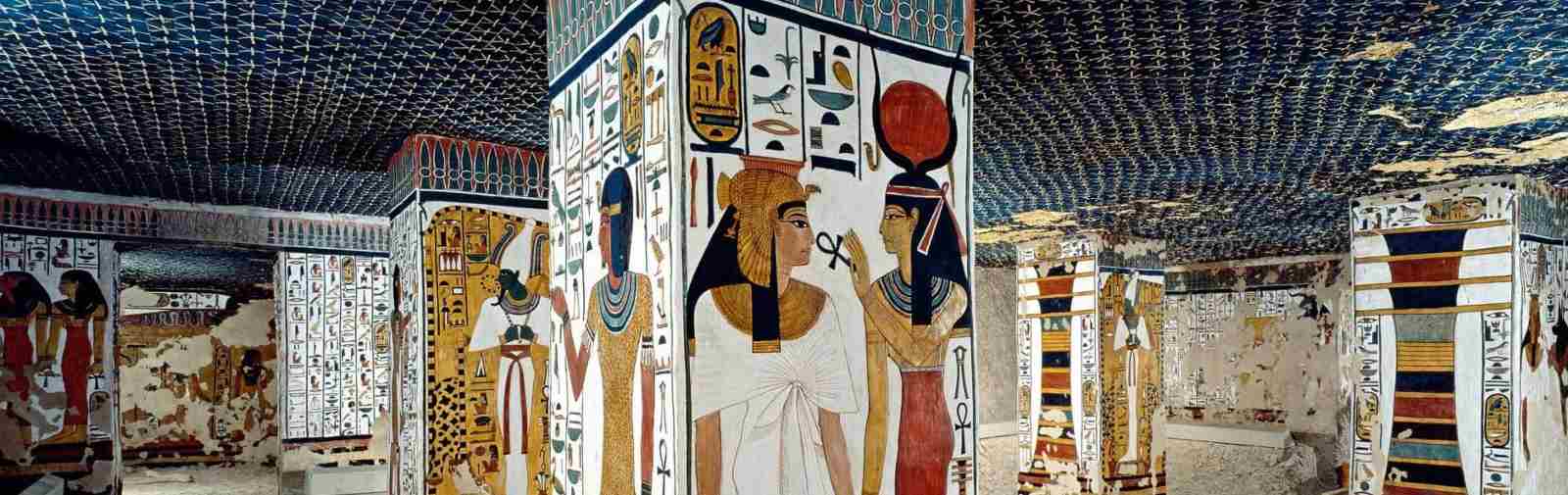

The ramp leading to the third terrace is flanked by Horus falcons. The Polish-Egyptian the mission has been working to restore the upper terrace at Deir el-Bahri since 1961 and it was closed to visitors until 2002. The pillars in the portico in front of the third terrace were decorated with Osirid statues of the queen, some of which have now been painstakingly restored.

Passing under a huge pink granite doorway the visitor enters a columned courtyard. The wall to the north of the doorway shows scenes from the ‘Beautiful Feast of the Valley’, with barques carrying statues of Tuthmose I, II, III and Hatshepsut. Barques of the Theban Triad are carried by priests, with offering-bringers, dancers and musicians making up the procession. The chambers in the northern part of the upper terrace is dedicated to the solar cult of Re-Horakhty and in one of these is a huge alabaster altar on which sacrifices would have been left exposed to the sun. Other niches and chapels (including another dedicated to Anubis and one to the parents of Hatshepsut) lead off from these chambers and still, have very well-preserved colourful paintings, but are still closed to visitors.

The southern side of the court in the upper terrace is dedicated to the royal mortuary cult. The wall to the south of the doorway also shows scenes of processions of royal statues in boats with their attendants. On the south wall are offering scenes to various deities. The chambers to the south of the court (still closed) included cult chapels of Hatshepsut and her father Tuthmose I with similar well-preserved decoration in each.

In the center of the upper court at the rear, is the sanctuary of Amun, the focus of the temple which was cut deep into the rock of the mountain (not at present open to visitors). This would have been the resting place for the barque of Amun during the ‘Valley Festival’. Two chambers in the sanctuary show scenes of Hatshepsut, with her daughter Neferure and Tuthmose III worshipping various gods. The sanctuary was later expanded by Ptolemy VIII, Euergetes who added a third chamber dedicated to Imhotep and Amenhotep son of Hapu who were worshipped as deities at this time and associated with gods of healing. The third terrace later became a sanatorium